Chapter 2 Question Formulation

Link to conceptual video: https://youtu.be/3TxiVitYYqQ

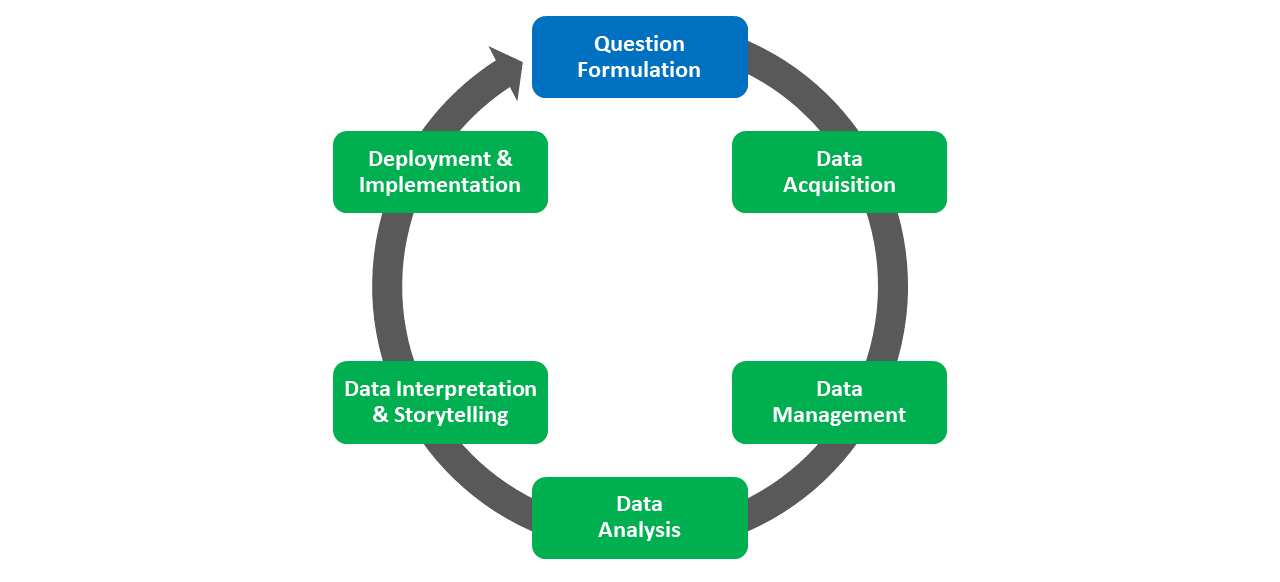

The first phase of the HR Analytics Project Life Cycle (HRAPLC) is Question Formulation. Question formulation refers to the process of posing strategy-inspired and -aligned questions or hypotheses (that can be answered using data) in order to investigate why or how a problem occurs, what a problem might lead to or be associated with, or who is affected by the problem. Thoughtful question formulation results in (a) more effective and efficient data acquisition, management, and analysis, and (b) answers that are more useful to stakeholders. Question formulation is closely associated with problem definition, which refers to the process of framing and diagnosing a problem (e.g., challenge, opportunity, threat) for which finding a solution will bring value.

2.1 Adopting a Strategic Mindset

When our goal is to improve the organization and the employee experience, adopting a strategic mindset sets us up for defining the right problems and formulating the right questions. A strategic mindset involves:

- Familiarity with strategic goals and roles, which requires recognizing and understanding strategic objects of the department and the organization, and the roles that key decision makers and stakeholders play.

- Understanding of organization systems, which requires the application of systems thinking when defining problems and formulating questions.

- Focus on opportunities for innovation, which requires thinking broadly and openly prior to narrowing focus.

- Application of (intellectual) curiosity, which entails asking “why”, “why not”, and “how” type questions.

2.1.1 Strategy

Because adopting a strategy necessitates an understanding of strategy, let’s take a moment to review the concept of a strategy. Simply put, a strategy refers to “a well-devised and thoughtful plan for achieving an objective” (Bauer et al. 2025, 35). Notably, a strategy is future oriented and provides a “roadmap” towards completion of a desired objective. Moreover, realizing a strategy requires coordinating business activities to achieve both short- and long-term objectives. When creating a new strategy, we often focus on two distinguishable phases: (a) strategy formulation and (b) strategy implementation.

2.1.2 Strategy Formulation

Strategy formulation involves “planning what to do to achieve organizational objectives – or in other words, the development and/or refinement of a strategy” (Bauer et al. 2025, 35–36). The prototypical strategy formulation often includes the following steps:

- Creating a mission statement, articulating a vision, and defining core values. The mission, vision, and values can serve as a compass by guiding organizational actions in the direction of a desired future state and by providing parameters and guidelines for reaching that future state.

- Analyzing the internal and external environments. Decision-making tools like a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis provide frameworks for understanding and describing the characteristics that are internal to the organization (e.g., employees) and characteristics that are external to the organization (e.g., labor market).

- Selecting a broad type of strategy. The type of strategy refers to the general approach an organization takes when bringing the mission, vision, and values to life, such as differentiation or cost leadership.

- Defining specific strategic objectives aimed at satisfying relevant stakeholders. This involves considering the needs of key stakeholders (e.g., customers, investors, shareholders, employees, broader communities) and considering what will result in a sustainable competitive advantage.

- Finalizing and temporarily “crystallizing” the strategy prior to strategy implementation. This step often results in a clear strategic plan that summarizes the previous four steps.

2.1.3 Strategy Implementation

Once we’ve completed the strategy formulation phase, we’re ready to move onto strategy implementation, where strategy implementation refers to the process of following through on the strategic plan developed and/or refined during the strategy formulation phase (Bauer et al. 2025). This phase involves building and leveraging the organization’s human capital capabilities in order to enact and realize the strategic plan, and aligning HR policies and practices with the strategic plan. For example, if a strategic objective outlined in the strategic plan requires acquiring, managing, or retaining the best software engineers, then the organization should focus on how HR systems like recruitment, selection, performance management, and reward systems can help support that requirement.

2.1.4 Strategic Human Resource Management

When HR management aligns with and supports the realization of organizational strategic objects, strategic human resource management emerges. In other words, strategic human resource management involves a strategy-oriented approach to human resource management. While most specific HR policies and practices will vary across organizations, there are practices that are generally strategically relevant for all organizations, and examples include selectively hiring new employees to ensure sufficiently high qualifications and good fit, and training employees to enhance job- and work-relevant knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) (Pfeffer 1998).

2.1.4.1 Video Lecture

Link to video lecture: https://youtu.be/08whYkgFiQI

2.2 Defining Problems & Formulating Questions

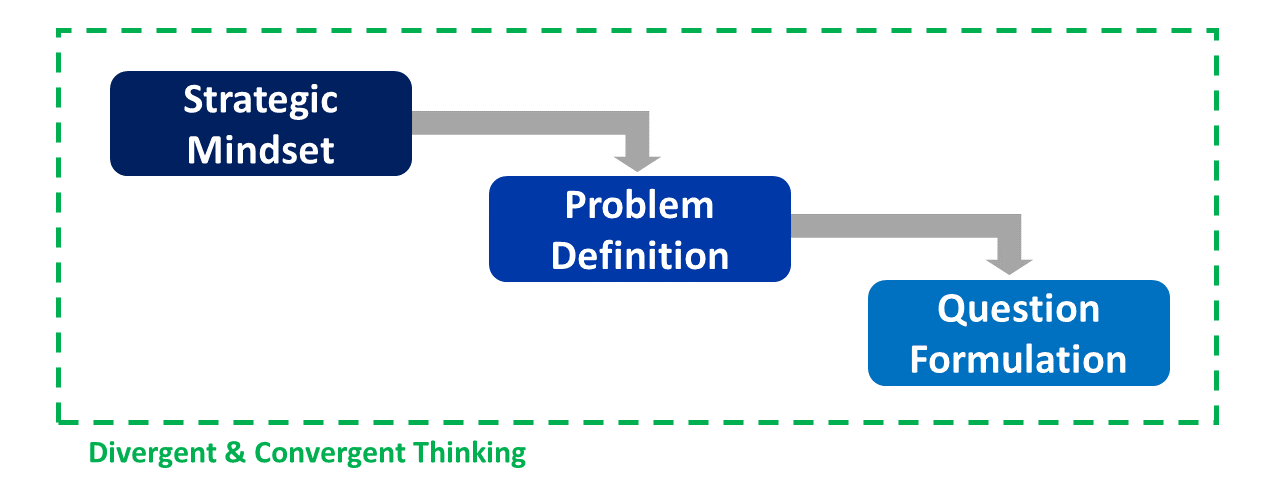

The overarching purpose of the Question Formulation phase of the HRAPLC is to define problems and formulate questions for which solutions and answers, respectively, can improve the organization and push it towards its goals. In the sections that follow, we will focus on the processes of problem definition and question formulation, and ultimately learn the value of applying both divergent and convergent thinking during both of these processes.

2.2.1 Defining a Problem

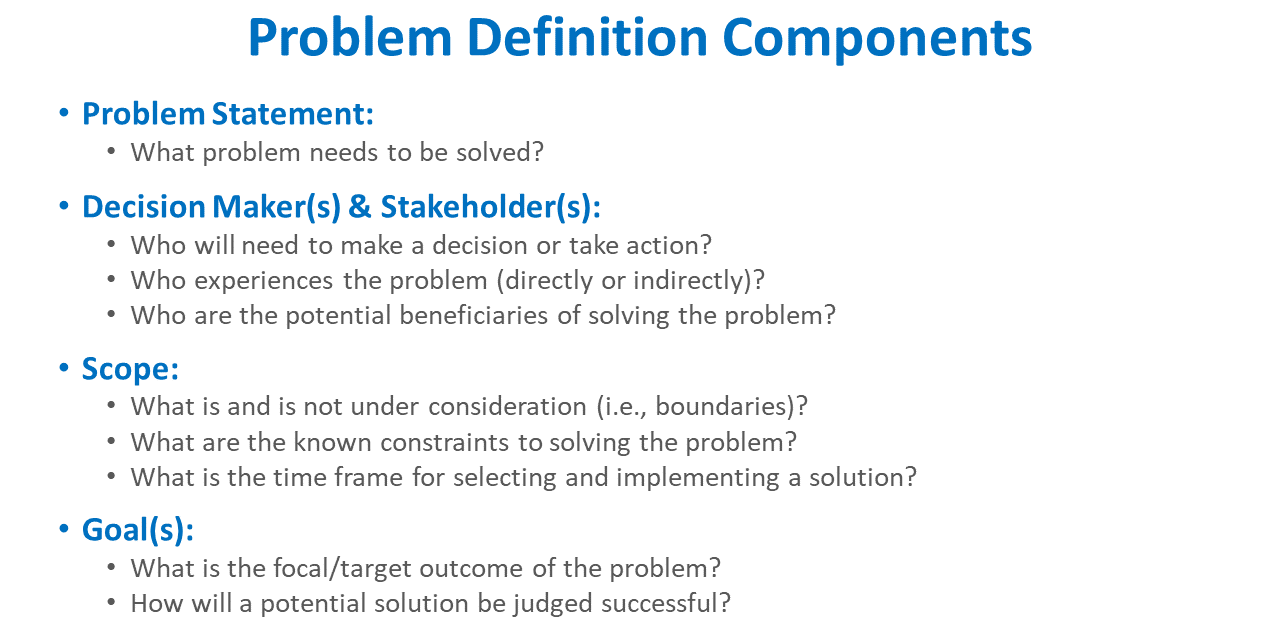

With a department’s and/or organization’s strategy in mind, we’re ready to define an organizationally relevant problem in need of a solution. While we typically know a problem when we see one, I found it’s helpful to take a step back and think about what a problem actually is. For our purposes, we can think of a problem as a gap between the current state of affairs and a desired state of affairs. Given that, problem definition refers to the process of framing and diagnosing a problem (e.g., challenge, opportunity, threat) for which finding a solution will be of value. As shown below, key problem-definition components often include articulating the problem statement, decision makers and stakeholders, scope, and goals (Chevallier 2016; Conn and McLean 2018).

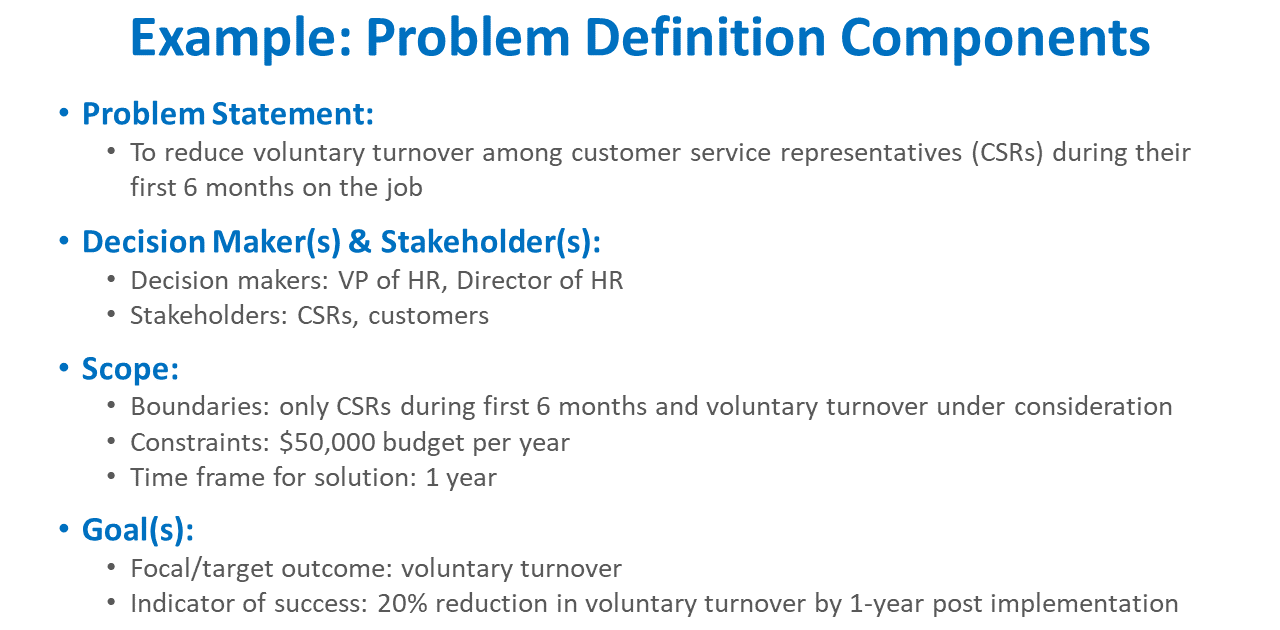

With respect to the HR context, in the figure below, I provide an example focused on the problem of voluntary turnover among new customer service representatives, and provide hypothetical examples of key problem-definition components.

2.2.2 Formulating a Question

Once a general problem has been defined, we’re ready to begin question formulation, which refers to the process of posing a question or hypothesis to investigate why or how a problem occurs, what a problem might lead to or be associated with, or who is affected by the problem. Question formulation can even help us flesh out the typical problem definition components outlined in the previous section. Just as we did with problem definition, we should continue to apply our strategic mindset when formulating questions. Moreover, we should focus on posing questions for which finding answers hold value for the organization, as doing so can contribute to the following (for example):

- a better understanding of the focal problem,

- the identification of potential solutions to the focal problem,

- solutions that meet the needs of key decision makers and stakeholders,

- more efficient and targeted literature searches and reviews, and

- more effective and focused storytelling.

So what is a question in this context? A question can be described as a general line of inquiry regarding a problem or phenomenon of interest. Examples of questions are as follows.

- What factors influence voluntary turnover?

- Does engagement predict voluntary turnover?

- How does engagement relate to voluntary turnover?

- Which work characteristics predict voluntary turnover?

- Why do new employees turn over in the first 6 months?

If, based on prior research or theory, an informed prediction can be made, we might choose to restate a question as a hypothesis, where a hypothesis can be thought of as a statement about an expected association, difference, change, or classification. Examples of hypotheses are as follows.

- Engagement is negatively related to voluntary turnover.

- Turnover intention mediates the relationship between engagement and voluntary turnover.

- Autonomy and task significance negatively predict voluntary turnover.

- New employees who participate in the formal onboarding program are less likely to quit during their first 6 months.

Regardless of whether we pose a question or state a hypothesis, it’s important to remember that question formulation is often an iterative process, which means that answering one question (or testing one hypothesis) often leads to additional questions (or hypotheses).

Further, we can draw upon existing theory and research to inform the types of questions we pose (or hypotheses we state). To learn about existing theories and relevant research for your phenomenon or topic of interest, we often perform a literature search and review of some kind. Please refer to the chapter on performing literature searches and reviews if you need additional tips on how to identify high-quality peer-reviewed research sources.

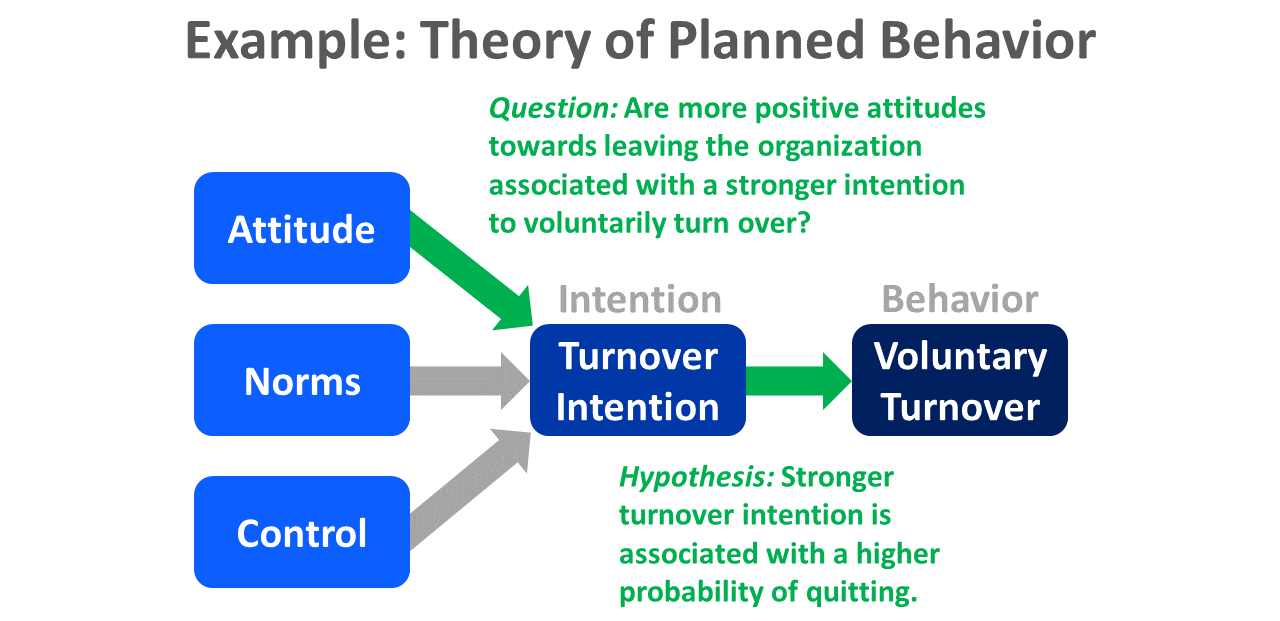

A theory provides a way to understand or explain a phenomenon of interest in a parsimonious manner. As an example, the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) is based on a voluminous body of research, and some of the basic tenets of the theory are as follows. First, an individual’s attitude towards a behavior, perception of the norms associated with the behavior, and sense of control over enacting a behavior contribute to their intention to perform a behavior. Second, an individual’s intention to perform a behavior often leads them to perform a behavior. This theory can be applied to any number of behaviors. Given that HR professionals (and organizational leadership) are often concerned with voluntary turnover (i.e., an employee-initiated organizational separation), let’s focus on voluntary turnover. Using the theoretical tenets, we can reason that an individual’s voluntary turnover behavior might be explained by their attitudes, norms, and sense of control related to voluntary turnover, and ultimately to their intentions to turn over voluntarily. Thus, based on the theory of planned behavior, we might first focus on the proposed link between attitudes and behavioral intention, and formulate the following question: Are more positive attitudes towards leaving the organization associated with a stronger intention to voluntarily turn over? Further, by focusing on the proposed link between behavioral intention and actually enacting the behavior, we might hypothesize the following: Stronger turnover intention is associated with a higher probability of quitting.

2.2.3 Thinking Divergently & Convergently

Throughout the processes of defining a problem and formulating a question, it is advisable to apply both divergent and convergent thinking. On one hand, divergent thinking refers to the process of adopting a broadened and imaginative mindset in which many ideas, possibilities, and alternatives are considered, which can lead to a large quantity of creative or novel ideas; on the other hand, convergent thinking refers to the process of adopting a critical and evaluative mindset in which various alternatives are judged, which can lead to a more refined set of high-quality ideas (Basadur, Graen, and Scandura 1986; Basadur, Runco, and Vega 2000; Reiter-Palmon and Illies 2004). When used effectively, these two ways of thinking can improve problem definition and question formulation.

More specifically, once we have adopted a strategic mindset, the identification, framing, and defining of problems should involve: (a) a phase of ideation with divergent thinking, such that many potential ideas, possibilities, and ultimately problems are entertained and considered –- with the primary focus being on novelty, creativity, and quantity; and (b) a phase with deliberate convergent thinking, such that the list of potential problems generated during the previous phase is winnowed to those that will contribute the most to the organization’s strategic goals, ends, or initiatives. A similar two-phase process can be applied when formulating questions.

2.2.3.1 Video Lecture

Link to video lecture: https://youtu.be/w1104yS-zJU

2.3 Summary

In this chapter, we did a conceptual deep dive into the Question Formulation phase of the HR Analytics Project Life Cycle. In doing so, we reviewed the importance of adopting a strategic mindset, and then engaging in thoughtful problem definition and question formulation. Finally, we learned how a two-phase process of deliberate divergent and convergent thinking can help us identify the most important problems and questions for which solutions and answers, respectively, would provide the most value to the organization.